The Archaeological Renaissance, as a style, emerged in the art of jewelry in the 19th century, antiquity has been in fashion since the time of Josephine, and the most fashionable jeweler working in the “antique style” was Fortunato Pio Castellani.

Biography

Fortunato Pio Castellani was born in 1794 to a family of jewelers and began his craft training in his father’s workshop. In 1814, Fortunato Pio opened a jewelry workshop in Rome on the ground floor of the Palazzo Raggi, ideally located on Via del Corso, a wide and unusually beautiful street that led into the heart of the historic center. It is known that the early works of his workshop in Rome were in the modern English and French style, but their origin cannot be established due to the unremarkableness and absence of the author’s stigma.

In 1826, Fortunato Pio met Michelangelo Caetani, Duke of Sermonet.

Caetani was a favorite of the Roman high society: politician, writer, talented artist and connoisseur of ancient jewelry art, scientist and Anglomaniac, he not only contributed to the establishment of business contacts with representatives of the highest aristocracy of England and France, but also took an active part in the creative activities of the company. Historians believe that it was Caetani who advised Fortunato Pio to pay attention to the work of ancient jewelers, and his creativity and connections helped Castellani reach unrivaled heights in jewelry making.

Castellani’s passion for excellence became an obsession and, as a result, led to the revival of many ancient technologies, thus making a great contribution to the Italian history of jewelry making. At the end of the 20s of the 19th century, Castellani began a revival of the classic, especially Etruscan, styles of jewelry production.

After the discovery in 1835 near the city of Cere (Cerveteri), the Etruscan tomb of the 7th century.

BC, named after its discoverers – the priest Regolini and General Galassi, the richest set of gold jewelry, as well as bronze and silver vessels were recovered. This territory was then part of the Papal States, therefore, the primary right to dispose of valuables belonged to Pope Gregory XVI.

Not without Caetani’s participation, Fortunato Pio Castellani, the founder and head of the Castellani Jewelry House, was invited as a restorer and consultant on the selection of jewelry pieces for the museum.

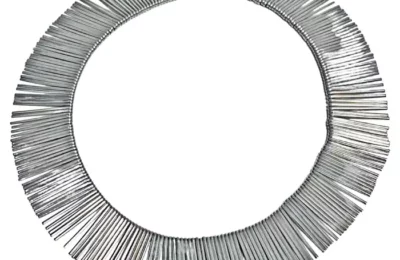

In 1836, the Italian jeweler Fortunato Pio set out to excavate an Etruscan tomb. Castellani is fascinated not only by the design of antique gizmos, but also by the way in which they were made. Of course, he began to try to make jewelry in the same style and using those old techniques. Castellani jewelry is made of finely wrought gold, often combined with delicate and colorful mosaics, carved stones or enamel, thus creating new trends in jewelry fashion.

In the 50s of the 19th century, his sons, Alessandro and Augusto, joined the business of Fortunato Pio.

At the same time, thanks to Caetani, Fortunato Pio and his sons gain access to a huge private collection of Roman, Etruscan and Ancient Greek jewelry, collected by the president of the Roman Academy of Archeology and papal treasurer, the Marquis Giovanni Pietro Campana.

The fate of the Marquis and his collection, alas, is sad. In 1854, due to serious financial problems discovered in the bank, accused of embezzlement and embezzlement of papal funds, he had to explain the origin of this jewelry collection, which apparently he succeeded badly, because three years later, the marquis was sentenced to twenty years in prison. imprisonment, later replaced by exile.

In 1859, the Marquis’s jewelry collection, confiscated by the Roman authorities, was handed over to the Castellani family for inspection and restoration.

Augusto Castellani had to prepare a catalog for the sale of the jewelry collection. Direct contact with the original jewelry allowed Castellani to experiment with new techniques for processing gold. They realized that ancient jewelers, to create a beautiful effect, added details to the metal, rather than using carving and stamping. Castellani were able to recreate the look of these antique jewelry using filigree. Castellani also revived wire weaving and beading. Part of the jewelry from the Marquis’s collection was copied, and a few months later, the main part was acquired by Napoleon III for the Louvre and exhibited there in 1862.